Die Spielregel (1939) Online

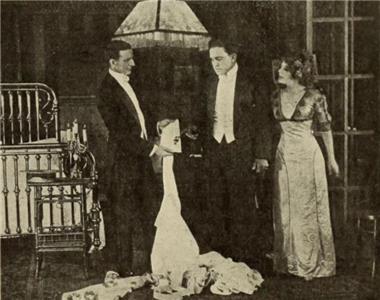

On the brink of WWII, the record-breaking aviator, André Jurieux, safely lands at a small airport crammed with reporters, only to come face to face with his worst fear: the object of his desire, Christine--a blonde noblewoman and wife of the affluent Marquis de la Cheyniest, Robert--is not there to greet him. Intent on winning her back, André accepts his friend Octave's invitation for a lavish hunting weekend at the aristocrat's palatial country estate at La Coliniere, among hand-picked guests and the mansion's servants; however, intrigue, rivalries, and human weaknesses threaten to expose both royalty and paupers alike. Who will breach the unwritten rules of the game?

| Cast overview, first billed only: | |||

| Nora Gregor | - | Christine de la Cheyniest (as Nora Grégor) | |

| Paulette Dubost | - | Lisette, sa camériste | |

| Mila Parély | - | Geneviève de Marras | |

| Odette Talazac | - | Madame Charlotte de la Plante | |

| Claire Gérard | - | Madame de la Bruyère | |

| Anne Mayen | - | Jackie, nièce de Christine | |

| Lise Elina | - | Radio-Reporter (as Lise Élina) | |

| Marcel Dalio | - | Marquis Robert de la Cheyniest (as Dalio) | |

| Julien Carette | - | Marceau, le braconnier (as Carette) | |

| Roland Toutain | - | André Jurieux | |

| Gaston Modot | - | Edouard Schumacher, le garde-chasse | |

| Jean Renoir | - | Octave | |

| Pierre Magnier | - | Le général | |

| Eddy Debray | - | Corneille, le majordome | |

| Pierre Nay | - | Monsieur de St. Aubin |

Despite now being considered by historians to be one of the best films ever made, the picture almost became a lost art. Claiming that it was bad for the morale of the country (due to impending war), the French government banned the film about a month after its original release. When Germany took over France the following year, it was banned by the Nazi party as well, who also burnt many of the prints. Allied planes then accidentally destroyed the original negatives. It was thought to be a lost picture. In 1956, some followers of director Jean Renoir found enough pieces of the film scattered throughout France to reconstitute it with Renoir's help. Renoir claimed only one minor scene from the original cut was missing.

When the film opened in 1939, initial reception of it was so bad that one viewer lit a newspaper and tried to burn the theater that it was playing in. There were even threats to other theaters.

The fact the movie was almost lost during the war is a myth: actually, the EXTENDED version was almost lost. The original movie shown in 1939 was 113 minutes, or maybe more. It was a relative failure, so Renoir cut it down to approx. 100 minutes and then again to 90 minutes (and even 85 minutes for theatres showing two movies). It was these 23 minutes that were thought to be lost during a WWII bombing. The situation remained unchanged until as late as 1958, when most of the original rushes were discovered and the long version reconstituted to 110 minutes, which is still the version showed nowadays. The parts that have been definitively lost correspond to two scenes for which sound exists, but not images.

The fact the movie was a complete failure when it came out in 1939 is partly a myth: it was a relative failure. Renoir himself thought it was a complete flop, but he was impressed by a few hostile reactions (which included fights and allegedly a man trying to set fire to a theatre). Attendance was low, but it was summer, there were political tensions with Germany and probably the public was put off by the turmoil around the movie. Critics were balanced: a study showed about a third were positive, a third negative and a third reserved. The movie was banned when WWII started and then again during German occupation, but so were other movies, e.g. the famous "Le Quai des brumes" (1938) and "Le Jour se lève" (1939), both by Carné.

After the success of La Grande Illusion (1937) and La Bête Humaine (1938), Jean Renoir and his nephew Claude helped set up their own production company, Les Nouvelles Editions Francaises. This was their first production.

Director Jean Renoir recut the film numerous times, due to poor initial reception and damage to the negatives during World War II.

"La Règle du jeu" is the only movie that has always been in the top 10 of Sight & Sound recurring poll "The Greatest Films of All Time": #10 (1952), #3 (1962), #2 (1972), #2 (1982), #2 (1992), #3 (2002), #4 (2012). ("Citizen Kane", for instance, was #11 in 1952. However it was then consistently #1 from 1962 to 2002 and #2 in 2012.)

Voted as the 4th greatest film of all time in Sight & Sound's 2012 critic's poll.

Was chosen by Premiere magazine as one of the "100 Movies That Shook the World" in the October 1998 issue. The list ranked the most "daring movies ever made."

Included in the Toronto International Film Festival's Essential 100, movies every cinephile should see.

The film is included on Roger Ebert's "Great Movies" list.

Included among the "1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die", edited by Steven Schneider.

Ranked number 5 non-English-speaking film in the critics' poll conducted by the BBC in 2018.

This film is part of the Criterion Collection, spine #216.

User reviews