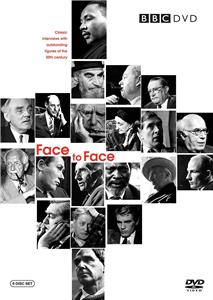

Face to Face Online

- Original Title :

- Face to Face

- Genre :

- TV Series / Documentary

- Cast :

- John Freeman,Norman Birkett,Robert Boothby

- Type :

- TV Series

- Time :

- 30min

- Rating :

- 8.6/10

| Series cast summary: | |||

| John Freeman | - | Himself - Presenter 35 episodes, 1959-1962 | |

User reviews