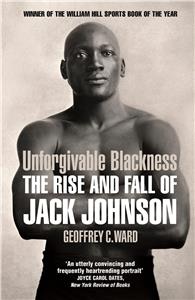

Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (2004) Online

- Original Title :

- Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson

- Genre :

- Movie / Documentary / Biography / Sport

- Year :

- 2004

- Directror :

- Ken Burns

- Cast :

- Jack Johnson,Keith David,Samuel L. Jackson

- Writer :

- Geoffrey C. Ward

- Type :

- Movie

- Time :

- 3h 34min

- Rating :

- 8.3/10

The story of Jack Johnson, the first African-American Heavyweight boxing champion.

| Cast overview, first billed only: | |||

| Jack Johnson | - | Himself (archive footage) | |

| Keith David | - | Narrator (voice) | |

| Samuel L. Jackson | - | Jack Johnson (voice) | |

| Adam Arkin | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Philip Bosco | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Kevin Conway | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Brian Cox | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| John Cullum | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Murphy Guyer | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Ed Harris | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Derek Jacobi | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Carl Lumbly | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Amy Madigan | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Carolyn McCormick | - | Other Voices (voice) | |

| Joe Morton | - | Other Voices (voice) |

User reviews