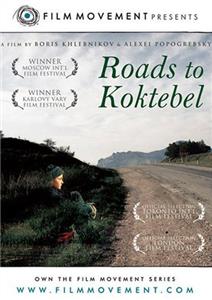

Koktebel (2003) Online

A widowed aeronautics engineer, who has lost his job, travels with his son hopping freight trains from Moscow to Koktebel, a town by the Black Sea, to start a new life with the father's sister. After they are stopped by a train guard, they continue their travel on foot. The father battles against his alcohol addiction and the son is fascinated with the idea of flight. One rainy day an old man accepts them in his house in return for the repair of the roof. The father gives in to the alcohol offered by the old man, who in a drunken brawl accuses him of stealing money and shoots him. A young female village doctor takes care of him and a romantic relationship between the two ensues. The father feels reluctant to continue the journey. The son leaves alone and a truck driver gives him a ride to Koktebel. However, his aunt has left for the summer.

| Cast overview: | |||

| Gleb Puskepalis | - | The Son | |

| Igor Chernevich | - | The Father | |

| Evgeniy Sytyy | - | Railway inspector | |

| Vera Sandrykina | - | Tanya | |

| Vladimir Kucherenko | - | Mikhail | |

| Agrippina Steklova | - | Kseniya | |

| Aleksandr Ilin | - | Truck driver | |

| Anna Frolovtseva | - | Tenant | |

| Lyubov Rozanova | |||

| Alexander Poslovsky | |||

| Sergei Kushnarenko | |||

| Sergey Shinkarenko | |||

| Yuri Panchishin | |||

| Tatiana Korol |

User reviews