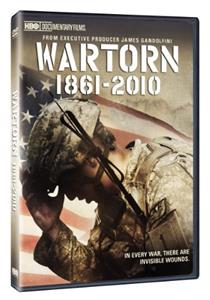

Wartorn: 1861-2010 (2010) Online

- Original Title :

- Wartorn: 1861-2010

- Genre :

- Movie / Documentary / War

- Year :

- 2010

- Directror :

- Jon Alpert,Ellen Goosenberg Kent

- Type :

- Movie

- Time :

- 1h 8min

- Rating :

- 7.8/10

With suicide rates among active military servicemen and veterans currently on the rise, the HBO special WARTORN 1861-2010 brings urgent attention to the invisible wounds of war. Drawing on personal stories of American soldiers whose lives and psyches were torn asunder by the horrors of battle and PTSD, the documentary chronicles the lingering effects of combat stress and post-traumatic stress on military personnel and their families throughout American history, from the Civil War through today's conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

For 50 plus years soldiers hooked on morphine ( new opiate to save lives during field operations) then the more heroic heroin were called "those with soldiers disease" . The government created these people to all but abandon them by leaving them in the wind.

User reviews