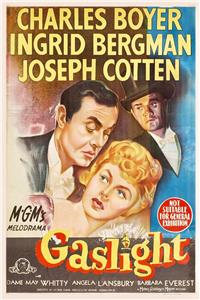

Years after her aunt was murdered in her home, a young woman moves back into the house with her new husband. However, he has a secret that he will do anything to protect, even if it means driving his wife insane.

Gaslight (1944) Online

After the death of her famous opera-singing aunt, Paula is sent to study in Italy to become a great opera singer as well. While there, she falls in love with the charming Gregory Anton. The two return to London, and Paula begins to notice strange goings-on: missing pictures, strange footsteps in the night and gaslights that dim without being touched. As she fights to retain her sanity, her new husband's intentions come into question.

| Complete credited cast: | |||

| Charles Boyer | - | Gregory Anton | |

| Ingrid Bergman | - | Paula Alquist | |

| Joseph Cotten | - | Brian Cameron | |

| May Whitty | - | Miss Thwaites (as Dame May Whitty) | |

| Angela Lansbury | - | Nancy | |

| Barbara Everest | - | Elizabeth | |

| Emil Rameau | - | Maestro Guardi | |

| Edmund Breon | - | General Huddleston | |

| Halliwell Hobbes | - | Mr. Muffin | |

| Tom Stevenson | - | Williams | |

| Heather Thatcher | - | Lady Dalroy | |

| Lawrence Grossmith | - | Lord Dalroy | |

| Jakob Gimpel | - | Pianist |

The first time Ingrid Bergman met Charles Boyer was the day they shot the scene where they meet at a train station and kiss passionately. Boyer was the same height as Bergman, and in order for him to seem taller, he had to stand on a box, which she kept inadvertently kicking as she ran into the scene. Boyer also wore shoes and boots with 2-inch heels throughout the movie.

Angela Lansbury was only 17 when she made this, her film debut. She had been working at Bullocks Department Store in Los Angeles and when she told her boss that she was leaving, he offered to match the pay at her new job. Expecting it to be in the region of her Bullocks salary of the equivalent of $27 a week, he was somewhat taken aback when she told him she would be earning $500 a week.

When this film was produced, MGM attempted to have all prints of the previous version, Gaslight (1940), destroyed. These efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, though the film was rarely seen for the next few decades.

Charles Boyer's wife, Pat Paterson was pregnant with what would be the couple's first and only child. Boyer and Paterson had been trying to have a baby for many years, and Boyer was exceptionally nervous while making this film. He would rush between takes to call and check on his wife's health as the expected birth date grew nearer. The baby was expected to come after Boyer had finished working on the film, but he arrived weeks early while Boyer was on set. The actor broke down in tears when he was notified, and he informed the rest of the cast and crew of his son's birth. Production was halted for the day and the cast and crew opened up bottles of champagne to celebrate the birth.

The film's screenwriter, John Van Druten, suggested that director George Cukor should offer screen-tests to some of Moyna MacGill's daughters for a role in the film. MacGill was a well-known English actress who had become a refugee during WWII. Angela Lansbury was the first of MacGill's daughters that Cukor auditioned. Lansbury had never acted in any capacity before her screen-test, but she wowed Cukor with her natural talent and professionalism. Cukor recalled that from the very first day on set, Lansbury was perfectly at ease and at home, even though she had no experience acting. He called her a natural-born actress.

Charles Boyer's contract stipulated top billing. When David O. Selznick heard this (Ingrid Bergman was under contract to him at the time), he refused to loan MGM Bergman's services. It was only after much pleading from Bergman, who was very keen to work with Boyer, that Selznick finally relented.

Ingrid Bergman spent some time in a mental institution to research her role, studying a woman who had suffered a nervous breakdown.

Named for this film, gaslighting has become a recognized form of controlling and manipulative behavior. It involves an exploitative person manipulating people who suspect him or her, into doubting themselves and questioning their own perceptions so that they distrust their own suspicions of the manipulator.

The movie won an Academy Award for set decoration. The gasoliers were real and the one in Charles Boyer's bedroom came from the 1872 Menlo Park, CA, mansion of Sen. Milton Latham, which was torn down in 1942.

The scene in which Angela Lansbury lights a cigarette in contradiction of Ingrid Bergman's wishes had to be postponed until toward the end of production. Lansbury was only seventeen when filming began and because she was a minor she had to be monitored by a social worker. The social worker refused to allow Lansbury to smoke while she was a minor, so the scene had to be postponed until her eighteenth birthday. When Lansbury walked on set on her birthday, Bergman and the crew had organized a party for her, and the cigarette scene was shot immediately after they celebrated her birthday.

George Cukor suggested that Ingrid Bergman study the patients at a mental hospital to learn about nervous breakdowns. She did, focusing on one woman in particular, whose habits and physical quirks became part of the character.

Although she eventually became very attached to the part and insisted on acting in this film, Ingrid Bergman was initially reluctant to take on the role of Paula. Bergman considered herself to be a very strong and independent woman, and worried that she would be unable to convincingly play the timid and fragile character. Bergman took great pride in her portrayal of a weak character and considered it one of her greatest challenges as an actress.

Ingrid Bergman found the beginning love scene with Charles Boyer so uncomfortable, because the two had just met prior to filming the scene, that she refused to do any other such love scene with someone she had just met for the rest of her career. When a similar situation arose with Anthony Perkins while she was filming Goodbye Again (1961), she asked Perkins to kiss her privately in her dressing room to prepare for the scene, so she would not be embarrassed and flustered while kissing him on screen.

Barbara Stanwyck was among those who Ingrid Bergman beat out for the Academy Award for Best Actress. Prior to the awards ceremony Stanwyck had been the rumored favorite to win the award for her performance in Double Indemnity (1944), and Bergman's victory had been considered a mild surprise. Stanwyck was gracious in defeat, however. She told the press that she was "a member of the Ingrid Bergman Fan Club." She concluded by saying that she didn't "feel at all bad about the Award because my favorite actress won it and has earned it by all her performances."

The sets are deliberately overfilled with bric-a-brac to emphasize Paula's increasing sense of claustrophobia.

The struggle between Charles Boyer, who wanted top billing for this film, and David O. Selznick, who strongly pushed for Ingrid Bergman to receive top billing, has been well-documented. In addition to Bergman's own ambivalence to the issue, director George Cukor's suggestion of "sandwich billing" helped to solve the problem. The "sandwich billing" practice of listing a well-known female star in between two popular male stars was a popular promotional technique for studios in the 1940s. Cukor explained to Selznick that he had used the "sandwich billing" method for Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story (1940) to great success. This argument eased Selznick's concerns of loaning Bergman to MGM and still allowed Boyer to receive top billing.

In her autobiography, Ingrid Bergman called Charles Boyer the most intelligent actor she ever worked with and one of the nicest. "He was widely read and well educated, and so different," she wrote.

Director George Cukor employed a story-telling method in order to get Ingrid Bergman in the right mindset as filming progressed. Each day, Cukor would recount the entire plot of the film to Bergman up to the point of the scenes they were set to film that day. Cukor felt the method was necessary, because the film was not shot sequentially and Bergman's character was supposed to change over time. Bergman quickly grew frustrated with the technique, and told Cukor "I'm not a dumb Swede, you've told me that before." The director ceased the story-telling for a few days until a producer notified Cukor of a sharp decline in acting quality in the daily rushes. The producer told Cukor that the actors appeared to be "acting as though they're under water." So, Cukor resumed his storytelling method, a practice Bergman soon grew to appreciate.

The aria that Ingrid Bergman is singing when we see her in the first scene of her in the present day is from the Gaetano Donizetti opera "Lucia Di Lammermoor". The opera is famous for its so-called "mad scene", in which the eponymous Lucia goes insane.

New scenes not in the original play were added to this version of "Gaslight", and the names of most of the characters were changed. The character that Joseph Cotten plays in this version was changed from a stout, humorously sardonic elderly man to a young, handsome one in order to serve as a potential love interest for Ingrid Bergman in the film, and in order to appeal more to the audience.

Director George Cukor asked producers to hire Paul Huldschinsky to help design the film's intricate Victorian sets. Huldschinsky was a German refugee who had fled his native country because of the war. He had been well-acquainted with upper-class European decor, because his family had accumulated wealth through their newspaper business and his wife was the heiress of a German railroad fortune. Huldschinsky had lost much of his material wealth when he fled to the United States, however had retained his eye for period decoration. He was working on rather routine, uncredited set dressings when Cukor tagged him for work on this film. The film's producers pushed for a more well-known and established set designer, but Cukor stuck with Huldschinsky. The gamble paid off as Huldschinsky's set designs won an Academy Award.

Most of the prints of Gaslight (1940) which survived the MGM's attempted eradication did so because they had been mistakenly labeled "Angel's Street", the title of the film's 1938 stage production.

The very distinctive brass bed (with a swan's-neck design) that is in Ingrid Bergman's hotel room near the beginning of the film was also prominently featured in Judy Garland's bedroom in Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

Ingrid Bergman won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in this film when The Bells of St. Mary's (1945) was being shot. In addition to Bergman, that film featured Academy Award-winning actor Bing Crosby and Academy Award-winning director Leo McCarey. During her acceptance speech, Bergman said "I am particularly glad to get the Oscar this time because I'm working on a picture at the moment with Mr. Crosby and Mr. McCarey. And I'm afraid if I went on the set tomorrow without an award, neither of them would speak to me."

Ingrid Bergman received the first of her three Academy Awards for her performance in this film.

Columbia Pictures initially bought the property as a vehicle for its contract player Irene Dunne, as the prospect of reteaming her with Charles Boyer was tempting. However, the studio sold the rights to MGM, which wanted to star Hedy Lamarr. Eventually Ingrid Bergman played the Paula role.

Angela Lansbury was required to wear platform shoes in order to appear taller, more domineering, and more sinister in comparison to Ingrid Bergman. Lansbury's added height drew even greater attention to Charles Boyer's diminutive stature, and added to the number of scenes in which Boyer was forced to stand on a box to increase his relative height.

MGM sued Jack Benny for infringement because he parodied this film in a segment called "Autolight" on his show, The Jack Benny Program (1950). The actor's legal team convinced MGM that the skit was in the realm of parody and therefore not a copyright violation. The studio begrudgingly dropped the suit.

The book from which Ingrid Bergman reads aloud is "Villette" by Charlotte Brontë.

The original Broadway stage play and source for the screen play was "Angel Street" by Patrick Hamilton which opened at the John Golden Theater on December 5, 1941 and ran for 1295 performances. The original stage cast included Leo G. Carroll, Vincent Price, and Judith Evelyn.

"Lux Radio Theater" broadcast a 60-minute radio adaptation of the movie on April 29, 1946 with Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer reprising their film roles.

The film takes place circa 1874. Mr. Anton begins to play the waltz: Die Fledermaus. He commented that is part of a new operreta written by Johann Strauss which premiered in 1874.

Both Irene Dunne and Hedy Lamarr turned down the chance to play Paula.

Both Joseph Cotton and Ingrid Bergman appear through courtesy of David O. Selznick.

Included among the "1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die", edited by Steven Schneider.

"The Screen Guild Theater" broadcast a 30-minute radio adaptation of the movie on February 3, 1947 with Charles Boyer reprising his film role.

This film received its initial telecast in Los Angeles Friday 11 October 1957 on KTTV (Channel 11), followed by Philadelphia Friday 10 January 1958 on WFIL (Channel 6), by New York City Sunday 2 February 1958 on WCBS (Channel 2), and by San Francisco 31 May 1958 on KGO (Channel 7).

Ingrid Bergman hated to begin shooting with a passionate love scene before she got to know her leading man better. But the first scene captured on film had her exiting a railway carriage and ending up in Charles Boyer's arms. It was an awkward moment for her, all the more so because Boyer was a few inches shorter than her and had to stand on a box for the scene.

The only film in which Ingrid Bergman gives an acting Oscar winning performance in a Best Picture nominee.

The only film to be nominated for Best Actor and Actress Oscars that year.

Industry rumors pegged Greer Garson as Ingrid Bergman's replacement if she had been unable to be loaned out for this film.

When Ingrid Bergman won the Best Actress Oscar for her performance in this film, she became the first actress to win the category against actresses who had all been nominated for Best Actress before.

In MGM's script, Charles Boyer was supposed to have told Ingrid Bergman at the end that he had loved her all along. This was an addition to the play made by the screenwriter. David O. Selznick, when reading over the script, was horrified and promptly sent MGM one of his famous long and involved memos, this one ordering the studio to omit the line, which it did.

User reviews