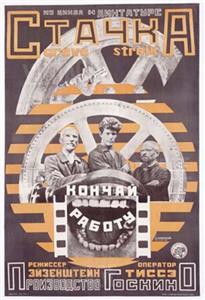

Stachka (1925) Online

In Russia's factory region during Czarist rule, there's restlessness and strike planning among workers; management brings in spies and external agents. When a worker hangs himself after being falsely accused of thievery, the workers strike. At first, there's excitement in workers' households and in public places as they develop their demands communally. Then, as the strike drags on and management rejects demands, hunger mounts, as does domestic and civic distress. Provocateurs recruited from the lumpen and in league with the police and the fire department bring problems to the workers; the spies do their dirty work; and, the military arrives to liquidate strikers.

| Complete credited cast: | |||

| Maksim Shtraukh | - | Police Spy | |

| Grigoriy Aleksandrov | - | Factory Foreman | |

| Mikhail Gomorov | - | Worker | |

| I. Ivanov | - | Chief of Police | |

| Ivan Klyukvin | - | Revolutionary | |

| Aleksandr Antonov | - | Member of Strike Committee | |

| Yudif Glizer | - | Queen of Thieves | |

| Anatoliy Kuznetsov | |||

| Vera Yanukova | |||

| Vladimir Uralskiy | - | (as V. Uralsky) | |

| M. Mamin | |||

| Rest of cast listed alphabetically: | |||

| Boris Yurtsev | - | King of Thieves |

First feature film directed by Sergei M. Eisenstein.

The earliest Russian-Soviet film included among the "1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die", edited by Steven Schneider.

User reviews