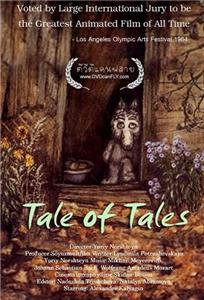

Skazka skazok (1979) Online

A reflection of Russian history and memory. Norstein creates a visual emotional response to a changing Russia, followed in the eyes of the Little Grey Wolf spying on various people's lives, and giving an insight on Russian culture in the 20th Century.

| Cast overview: | |||

| Aleksandr Kalyagin | - | Little Grey Wolf (voice) |

The title of the film, and partial inspiration, came from a poem by Nazim Hikmet. The original title "The Little Grey Wolf Will Come" was rejected by censors.

Named the greatest animated film of all time by the 1984 Animation Olympiad jury held in conjunction with the 1984 LA Olympics.

Among the innovative ideas of Norstein is the image of people in animation.

According to its poetics, as well as the techniques used, the film is close to the films of Andrey Tarkovskiy, the drawing of Pablo Picasso, and Japanese painting.

Norshtein repeatedly stressed that the animated film is an autobiographical tape.

Film scholars pay attention to the visual blurring of the characters in the film, as well as the lack of precise contours between objects in the film.

Fipresci Jury Award (Yuriy Norstein) at the V International Animated Film Festival in Zagreb, 1980.

Grand Prix at the International Film Festival of Short Films and Documentary Films in Lille (France), 1980.

Prize of the International Federation of Film Clubs in Oberhausen (Germany), 1980.

First Prize (Yuriy Norshtein) at the International Film Festival of Animated Films Ottawa (Canada), 1980.

2-place in the ranking of "150 best animated films of all time in Japan and the world", Tokyo, 2003.

The creator of the film broke the tradition - he took as a basis the sketch's style, close to Picasso's graphic works or Pushkin's ink drawings. As a result, a balance was formed between fantastic conventionality and natural organicity.

User reviews