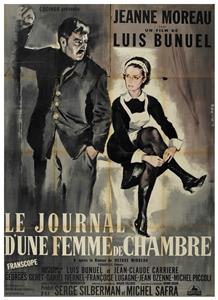

Diary of a Chambermaid (1964) Online

Celestine, the chambermaid, has new job on the country. The Monteils, who she works for are a group of strange people. The wife is frigid, her husband is always hunting (both animals and women) and her father is a shoe-fetishist. Joseph, the farm-labourer is a fascist and sexually attracted to Celestine. Celestine settles herself and talks to the neighbour, an ex-officer, who likes damaging his neighbour's things. After the death of the old man, she quits her job, but because of the rape and murder of a child 'Little Claire' she decides to stay, believing that Joseph is the murderer. To get his confession she sleeps with him and promises to marry him. In spite of her engagement she fakes evidence to implicate him in the murder. He is arrested, but is released because the evidence is inconclusive. She marries the ex-officer and takes on a housewife role similar to that of Madame Monteil.

| Cast overview, first billed only: | |||

| Jeanne Moreau | - | Céléstine | |

| Georges Géret | - | Joseph | |

| Daniel Ivernel | - | M Mauger | |

| Françoise Lugagne | - | Mme Monteil | |

| Muni | - | Marianne | |

| Jean Ozenne | - | M Rabour | |

| Michel Piccoli | - | M Monteil | |

| Joëlle Bernard | - | (as Joelle Bernard) | |

| Françoise Bertin | |||

| Jean-Claude Carrière | - | Le curé | |

| Aline Bertrand | - | La voyageuse | |

| Pierre Collet | - | Le voyageur | |

| Michel Dacquin | - | (as Michel Dacquid) | |

| Madeleine Damien | - | La cuisinière des Monteil | |

| Marc Eyraud | - | Le secrétaire du commissaire |

The demonstrating fascists shout "Vive Chiappe", a homage to the chief of the Parisian police who prohibited showing director Luis Buñuel's earlier film Hrysi epohi (1930) after fascists destroyed the cinema where it was being shown.

This is Luis Buñuel's only film in the anamorphic widescreen format.

The protest at the end of the film, is based on a real protest which took place in 1934. The Far-right leagues (Ligues d'extrême droite) were protesting about the removal of Jean Chiappe from his position as Prefect of Police by Édouard Daladier, president of the Conseil (Council), France's governing body.

This film is part of the Criterion Collection, spine #117.

User reviews