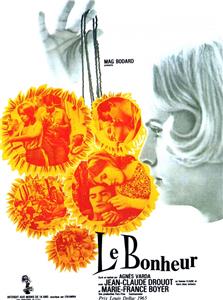

François, a young carpenter, lives a happy, uncomplicated life with his wife Thérèse and their two small children. One day he meets Emilie, a clerk in the local post office.

Glück aus dem Blickwinkel des Mannes (1965) Online

Francois is a young carpenter married with Therese. They have two little children. All goes well, life is beautiful, the sun shines and the birds sing. One day, Francois meets Emilie, they fall in love and become lovers. He still loves his wife and wants to share his new greater happiness with her.

| Complete credited cast: | |||

| Jean-Claude Drouot | - | François Chevalier | |

| Marie-France Boyer | - | Émilie Savignard | |

| Marcelle Faure-Bertin | - | (as Marcelle Favre-Bertin) | |

| Manon Lanclos | |||

| Sylvia Saurel | |||

| Marc Eyraud | - | J. Forestier - le frère de François | |

| Christian Riehl | |||

| Paul Vecchiali | - | Paul |

The movie François and Therese are going to see starring Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau is Viva Maria! (1965)

User reviews